An Analysis of Croatian Families in the 1910 United States Federal Census of Duquesne, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania ~ by Patricia J. Angus

Approximately one hundred years ago, Carnegie’s Kingdom of Steel bourgeoned along the banks of Pittsburgh’s rivers. Despite slow means of communication and travel, laborers from many European nationalities answered the call of the New World and flocked to furnaces of opportunity, such as the emerging Duquesne Steel Works. Initially the Irish, Welsh, Swedes, and Germans came to find employment, and by 1910 they were joined by Italians, Russians, Lithuanians, Hungarians, Slovaks, Serbs — and Croatians.

I grew up believing that Croatians made up a vast majority of these newcomers. Why would I even consider otherwise? Four of my great-grandparents were among those Croatians who first immigrated to Duquesne. My young world revolved around Tamburitza music, weddings at the American-Croatian Club, and “laku noć” (good night) at bedtime. Didn’t everybody celebrate Labor Day weekend by eating lamb at Green Gables and kolo dancing in the picnic pavilions at Kennywood Park? Just how many Croatian immigrants lived in Duquesne at the turn of the twentieth century? An analysis of the 1910 United States Federal Census might help us draw more accurate conclusions about the early Croatian immigrants to the city of Duquesne. Although census records are typically not considered primary sources due to the high probability of errors; census data may assist us in identifying overall population trends within the community.

The 1910 census is the preferred enumeration year for two specific reasons. 1.) According to census records, the population of Duquesne, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania surged between the years of 1900 and 1910, with the addition of nearly 6700 additional inhabitants, bringing the city’s population to over 15,700 people. Much of this increase was due to the immigration of laborers to meet the needs of the steel industry. 2.) Due to this tremendous influx of immigrants, census takers were required to specifically list the country of origin. For example, at that time many countries, including Croatia, were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Prior to 1910, the country of origin for a Croatian might be enumerated as “Austrian”. But in the 1910 enumeration a Croatian was listed as “Hun-Croatia”, “Aust-Croatia”, or “Horvat” (originating from the word hrvat, meaning Croatian). By 1920, after WWI, Croatians are listed in the broader category of “Yugoslavian”, making it more difficult to assess the Croatian migration.

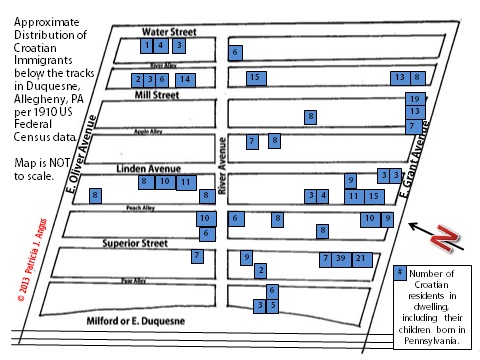

I used this terminology to identify Croatians in my personal study of the 1910 United States Federal Census. Surprisingly, these records indicate that the melting pot in Duquesne was characterized by only a smidgeon of Croatian – identifying a mere 401 individuals that were Croatian immigrants living in the city of Duquesne, including their Pennsylvania born children. That means Croatians represented only 2.55% of Duquesne’s population at the time. Over 96% of these earliest Croatian immigrants were living in the neighborhood “below the tracks” on the north side of the mill! The other 4% consisted of three families and a couple boarders (15 people total) sprinkled in other parts of the city. Therefore, most Croatians were conglomerated amid people of other nationalities in their new home along the river. For the most part, Croatians lived with or around other Croatians, although a few households shared accommodations with Hungarian and Slovak families. Below is a map showing the approximate distribution of Croatian immigrants in the neighborhood below the tracks of Duquesne in 1910.

1910 Distribution Map of Duquesne’s Croatian Immigrants

(See also Penn State University Libraries, Digital Collection — Maps of Duquesne, Allegheny, Pennsylvania)

Most families made room for additional boarders in their households. Women cooked, cleaned, shopped, and laundered for their families as well as for the boarders. Everyday appliances were not yet available – -no microwaves, automatic washers or dryers. No ice boxes or refrigerators! In all but two cases, women’s occupations were enumerated as “none” on the census records. Somehow I don’t believe that they did nothing. I am sure that Mrs. Stipetich and the other two women living at 19 Superior Street did their share of “work” with 39 residents to feed! How many rolls of sarma (cabbage rolls) does it take to feed 3-dozen hungry laborers? The two exceptions to occupations of “none” were two single Croatian women employed as servants, one to a private family and the other serving in a boarding house. Essentially all the women were laboring at household tasks to accommodate the needs of children and the men laboring outside of the home.

The women’s contributions were necessary in order to sustain the 225 male boarders who made up over half of the Croatian immigrant population. Although most boarders were single males, about 40% were married and living away from their families, and almost all earned a living by working in the steel mill or on the railroad. Census records indicate that the boarders spanned in age from as young as 17 years old and as old as 56, with the median age somewhere around 28 years old. This is similar to the average age for the head of household in the Croatian immigrant families which calculated out to be approximately 29 years of age. Many households were maintained by newlywed couples still in their early twenties with heads of households also working for the steel mill or railroad.

Everyone rented their property according to the enumeration. Not one Croatian family in Duquesne owned their own home in 1910; however four individuals operated businesses in the community. These four individuals were identified as proprietors of businesses:

- Joseph Mostic and Michael Obradovich of 33 Pear Alley ran their own baker shop.

- Mike Divjak of 3 Linden Avenue was a grocery store merchant.

- Steve Babic of 109 Linden was a liquor dealer.

The names and information about these business proprietors may or may not be accurate depending upon the amount of miscommunication between the resident and enumerator. English-speaking census takers were bombarded by a cacophony of foreign languages and dialects as they collected information. In addition, many of the immigrants did not speak English or were illiterate even in their native tongue. This is exemplified in the census data pertaining to my great-grandparents. My great-grandfather Matt Salopek is identified as Mike on the 1910 census, and his son Anthony, my grandfather, is listed as Andy. Anthony and Andy could sound very similar if spoken with an unfamiliar accent. Therefore, the recorder simply wrote the name that he or she perceived on the form. My Kučinić great-grandparents lived near the Salopeks, but they were more difficult to locate in the census records due to the incorrect spelling of their surname. Digital searches using the alternate spellings of “Kucanic” or “Kuchinich” did not produce results. Finally I located them with the names of Mike and Annie “Cutanitz”, again spelled according to best determination of the enumerator. Of course, over time surnames also changed to American variants which present even greater research challenges.

Life’s circumstances equally changed. Neither of my two families, mentioned above, remained in Duquesne throughout their lifetimes. Matt and Agnes Salopek returned to their village in Croatia and remained there for the rest of their lives. One of their children stayed in Duquesne, and three of them returned to Duquesne in their adulthood. Annie’s husband Mike Kučinić died at age 31 and is buried in an unmarked grave in St. Joseph’s Cemetery. Annie remarried and relocated to Washington, Pennsylvania, leaving her four oldest children to be raised with family in Croatia; one of those children, my grandmother, returned to Duquesne 20 years later. The stories of my ancestors might belong to any number of Croatian families represented in the 1910 census. World War I, financial difficulties, personal afflictions as well as new opportunities resulted in the relocation of individuals and families. Croatians came, and some of them stayed in Duquesne. Some departed and were gone forever. Others left and returned.

It took several generations for our Croatian families to become permanently fixed in American soil. The earliest immigrants planted seeds along the banks of the Monongahela, and through the decades their posterity grew and eventually spread up the hill and outward to all parts of the United States. Nevertheless, succeeding generations remain anchored by those roots that sprang from a little community of Croatians who elected to live below the tracks a century ago.

(c) 2013 to present Patricia J. Angus

Search for your Duquesne Ancestors for FREE at FamilySearch

BROWSE the 1910 United States Federal Census for FREE at FamilySearch

As an example, my Croatian grandfather’s name was Ivaniš; all his family in this country now use the spelling Evanish, as close as possible to the original pronunciation. Grandma’s maiden surname was Baša; all her American family adopted Barsh.

Regarding their travels, my great-grandfather and grandfather came to this country and returned TWICE to Bubnjarci, and on the 3rd trip, my great-grandfather returned and Grandpa stayed, first working in Pueblo, CO, before settling in Turtle Creek.

LikeLike

Did they talk much about their lives and travels, Lou? My grandparents never said much. I think perhaps it saddened them too much or they were afraid to share the information for some reason. Thanks for your comments.

LikeLike

Lou, my last name is Evanish. Both my grandparents moved from Penn to Micigan. Is it possible that I msy have other relatives living in Penn?

LikeLike